The $98k figure probably represents Nishimatsu's base pay, which is substantially padded by numerous perks. Still, "according to the consultancy Towers Perrin, CEOs of big Japanese companies earned an average $809,000 in 2003 — chump change compared with the $11.4 million raked in by their average U.S. counterpart," notes USA Today.

The smirking tone of the article suggests that the Japanese are out of step, that society here undervalues corporate leadership. It seems though, Japan has a far healthier attitude toward compensation and social cohesion than the USA, where the underlying operating principle in business seems to be to get as much as you can as quick as you can by whatever means necessary and damn those around you who aren't strong enough or shrewd enough to compete.

Except for young executives with a foot already on the career ladder, or those making a living off investing, I can't see that the average American could take issue with executives making less and sharing more with those further down the chain of command. But somewhere along the way citizens have been trained to believe the economy and the entire world free enterprise structure would collapse if CEOs were offered less.

Perhaps they imagine these guys (and its still mostly guys) indignant at offers of 10million instead of 100million, leaving in an insulted huff to go fishing rather than squandering their talent for so little reward. But really, what else would they do? If the salary bar were lowered, most would go on doing the same and be happy because they would still be making more than anyone else, which is what the outrageous compensation packages seem to be all about.

Quite unintentionally, I found in the same day's news an essay first written in 1966 (recycled through a blog via Google News) positing a more rational approach to economics, specifically in our underlying assumptions of value.

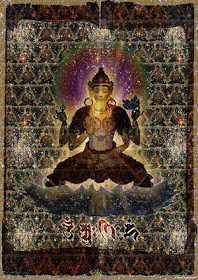

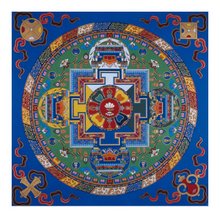

[The modern economist] is used to measuring the "standard of living" by the amount of annual consumption, assuming all the time that a man who consumes more is "better off" than a man who consumes less. A Buddhist economist would consider this approach excessively irrational: since consumption is merely a means to human well-being, the aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption.

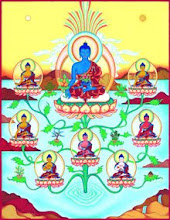

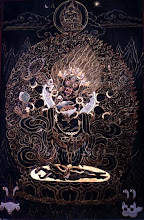

The optimal pattern of consumption, producing a high degree of human satisfaction by means of a relatively low rate of consumption, allows people to live without great pressure and strain and to fulfill the primary injunction of Buddhist teaching: “Cease to do evil; try to do good.” As physical resources are everywhere limited, people satisfying their needs by means of a modest use of resources are obviously less likely to be at each other’s throats than people depending upon a high rate of use.

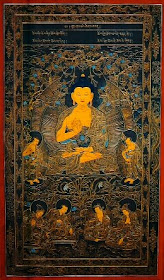

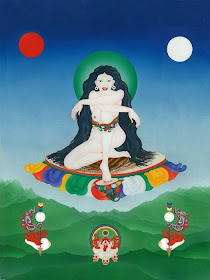

Buddhist Economics

By E. F. Schumacher

What if those CEOs did leave and go fishing? We might miss out on a few innovations, but we'd survive just fine and perhaps in the process create a saner, healthier, happier living environment. And after a generation or two, no one would imagine that things could or should be any different.

#

0 comments:

Post a Comment